The Oldest Minerals on Earth Are Rewriting the Planet’s Origin Story

Tiny zircon crystals are revealing that Earth’s earliest history may have included surprisingly complex tectonic activity.

Earth today is built around recycling. Old crust sinks, melts, and returns as new rock. A new zircon study suggests that kind of cycling may have started shockingly early, in some places, when the planet was still in its first half billion years.

Scientists led by the University of Wisconsin–Madison found distinctive chemical patterns inside zircons, Earth’s oldest minerals, that match what geologists expect from subduction and from large amounts of continental crust during the Hadean Eon, more than 4 billion years ago.

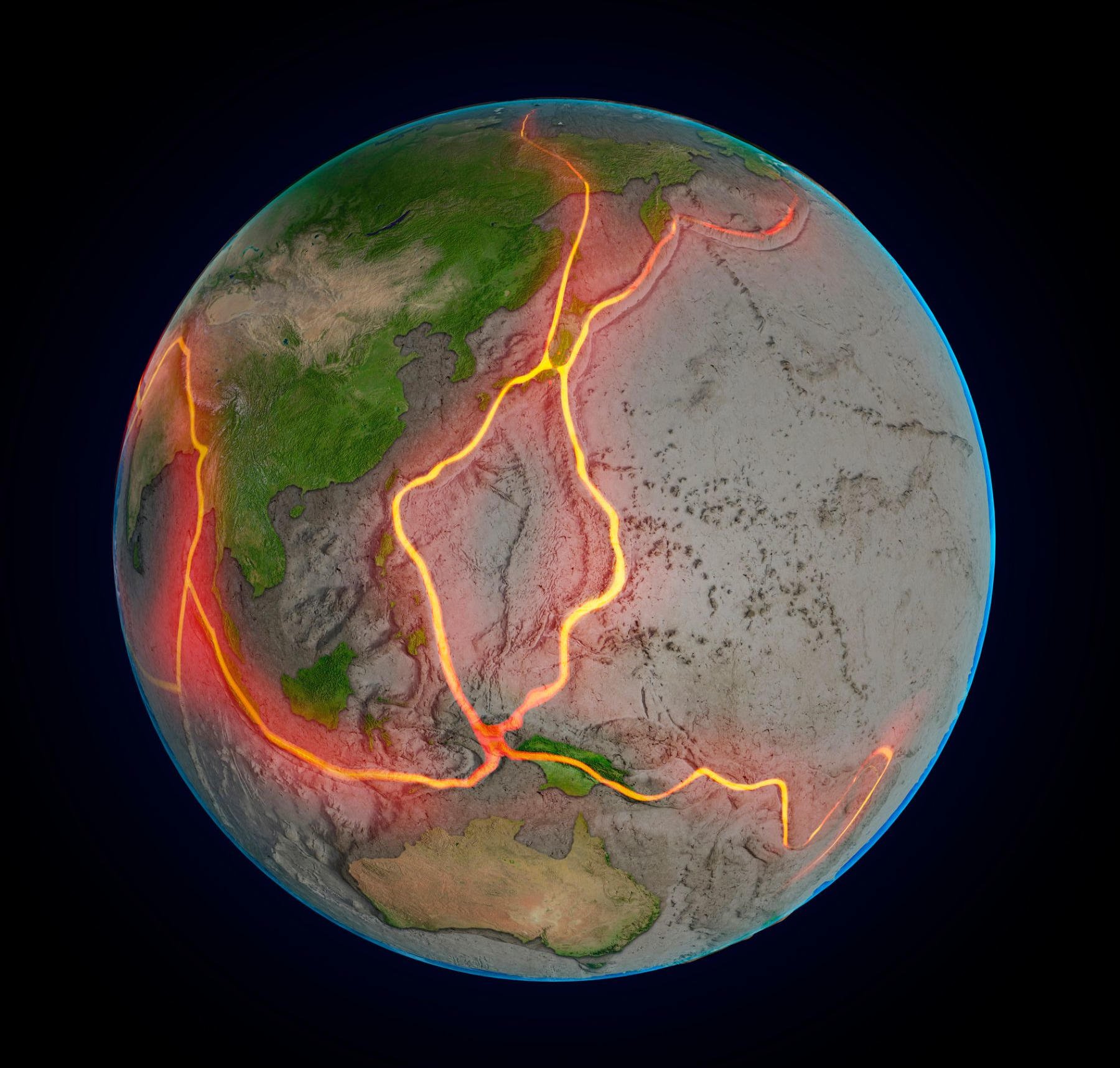

If that interpretation holds, the early Earth was not simply wrapped in a rigid, motionless outer shell, the classic “stagnant lid” idea that also assumes little or no continental crust. Instead, at least some regions may have been dynamic enough to reshape the surface, which matters because crust recycling and continent building influence where stable, potentially life-friendly environments can exist.

The work was published in Nature and focuses on ancient zircons from the Jack Hills of Western Australia. These grains, often found as tiny crystals weathered out of older rocks and preserved in younger sediments, are prized because they carry the only direct record from Earth’s first 500 million years. That makes them rare witnesses to how the surface and interior interacted as the earliest continents began to take form.

High-Precision Chemical Fingerprinting

The research team reached its conclusions by measuring trace elements inside individual zircon grains using WiscSIMS, a highly sensitive instrument located at UW–Madison. This technology allows scientists to analyze objects roughly one-tenth the width of a human hair. The team also developed new analytical techniques that made it possible to measure elements that could not be reliably studied before.

The trace elements serve as chemical markers that reveal the conditions under which each zircon formed. By examining these signatures, researchers can tell whether a zircon crystallized from magma rising directly from the mantle beneath Earth’s crust or from magma linked to subduction and continental crust. Zircons retain their original chemical makeup when they form and are extremely resistant to later changes, making them some of the most dependable record-keepers of early Earth processes even billions of years later.

“They’re tiny time capsules and they carry an enormous amount of information,” says John Valley, a professor emeritus of geoscience at UW–Madison who led the research.

Evidence for Early Continental Crust

According to Valley, the chemical composition of zircons from the Jack Hills indicates that they formed from a very different source than other Hadean zircons discovered in South Africa. The South African samples show chemical traits typical of simpler rocks that originated deep within Earth’s mantle.

“What we found in the Jack Hills is that most of our zircons don’t look like they came from the mantle,” says Valley. “They look like continental crust. They look like they formed above a subduction zone.”

Together, the two zircon populations suggest that Earth’s earliest geology was more varied than previously assumed, with different tectonic processes operating at the same time rather than a single, uniform system, Valley says.

“I think the South Africa data are correct, and our data are correct,” Valley says. “That means the Hadean Earth wasn’t covered by a uniform stagnant lid.”

Importantly, the type of subduction that could have produced the Jack Hills zircons is not necessarily the same as in modern plate tectonics. Valley described a process in which mantle plumes of ultra-hot rock rose, partly melted, and pooled at the base of the crust, creating circulation that could draw surface materials downward.

“That is subduction,” he says. “It’s not plate tectonics, but you have surface rocks sinking down into the mantle.”

This matters because subduction carries water-rich surface rocks down to hotter depths, where they can cause melting and form magmas that produce granitic rocks.

“If you have material on the surface, the surface had liquid water in the Hadean,” Valley says. “And when you take that material down, it’s wet and dehydrates. The water causes melting and that forms granites.”

Building the First Continents

Granites and related rocks are fundamental building blocks of continents. They’re less dense than other common rocks found under Earth’s oceans. This creates buoyant continents that rise higher above the ocean basins, providing stable environments on the Earth’s surface.

“This is evidence for the first continents and mountain ranges,” Valley says.

The results suggest that early Earth was geologically diverse, with different tectonic styles operating simultaneously in different regions.

“We can have both a stagnant-lid-like environment and a subduction-like environment operating at the same time, just in different places,” Valley says.

That complexity could reshape how scientists think about the planet’s first billion years, and the implications extend beyond tectonics. Subduction and continent formation influence when dry land first appeared and how surface environments evolved.

“What everybody really wants to know is, when did life emerge?” Valley says. “This doesn’t answer that question, but it says that we had dry land as a viable environment very early on.”

The oldest accepted microfossils are about 3.5 billion years old, but the Jack Hills zircons push evidence for potentially habitable surface conditions much earlier.

“We propose that there was about 800 million years of Earth history where the surface was habitable, but we don’t have fossil evidence and don’t know when life first emerged on Earth,” Valley says.

Looking Deeper Into the Hadean

As scientists continue to hunt for evidence of what the earliest Earth was like, Valley says the latest results are an example of the power of improving and refining laboratory techniques.

“Our new analytical capabilities opened a window into these amazing samples,” he says. “The Hadean zircons are literally so small you can’t see them without a lens, and yet they tell us about the otherwise unknown story of the earliest Earth.”

Reference: “Contemporaneous mobile- and stagnant-lid tectonics on the Hadean Earth” by John W. Valley, Tyler B. Blum, Kouki Kitajima, Kei Shimizu, Michael J. Spicuzza, Joseph P. Gonzalez, Noriko T. Kita, Ann M. Bauer, Stephan V. Sobolev, Charitra Jain, Aaron J. Cavosie and Alexander V. Sobolev, 4 February 2026, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-10066-2

This research was supported by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon H2020 research and innovation program (856555) and the National Science Foundation (EAR-2320078, EAR-2136782).

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.

Source link